Mike Ruggeri Reports

KEEPING AN EYE ON ARCHAEOLOGY NEWS & EVENTS

New and Dynamic Research

on the Peopling of the Caribbean

Previous non-genetic studies of the ancient settlers of the Caribbean Islands pointed to perhaps a single immigration of the Caribbean by people from either Central or South America. Since earlier research depended on non-genetic study of artifacts like tools, pottery, bone and shell fragments, these studies did not have the advantage of the more sophisticated genetic and DNA analysis. Now these techniques have been applied to this question for the first time, and the results are far reaching and dynamic in answering the questions of who the first Caribbean peoples were.

Two new studies using advanced genetics in Copenhagen, Leiden, and Harvard Medical School have been published recently in the journal Nature, and in the journal Science. While both papers differ in only one important aspect which I will discuss, both have reached the same overall conclusions independent of each other.

The two groups of researchers studied the genomes of 263 individuals. The genomes researched were of people in the Caribbean and Venezuela. The genome study revealed that the Caribbean was populated in two waves from Venezuela and Central America, and the first wave came into the Caribbean 3,100 years before the second wave. They extracted DNA from the bone protecting the inner ears of these individuals since the humid weather decayed the rest of the DNA in their systems.

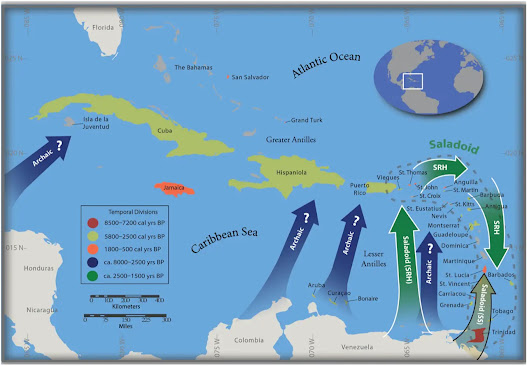

The first people to enter the Caribbean were a stone tool using tribe that entered Cuba 6,000 years ago and expanded eastward to other islands, probably originating in Belize because their artifacts look like Belize artifacts.

The second wave entered 2,500-3,000 years ago and were farmers and potters related to the Arawak of northeast South America who traveled to the Venezuelan coast and then to Puerto Rico and westward starting in what is called the Ceramic Age.

Traces of the oldest inhabitants from the first wave can be found in western Cuba. These two groups rarely mixed, the genetic record shows. The settlers spread to some 700 islands in the Caribbean. And although European diseases and conquest wiped out the small populations on these islands, researchers found 4% of their genes in Cuba, 6% in the Dominican Republic and 14% in Puerto Rico.

The researchers who published their paper in Science found genetic traces of Channel Islanders off the coast of California, which has a record of settlement going far back in history to at least 12,000 years ago. They would have traveled south in the Pacific and then their tribe would have traversed Venezuela to the Caribbean.

The group that published their paper in Nature did not find these genetic materials. The full Nature research paper is published online for free here: <https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-020-03053-2>. The dense genetic science in that paper gives you an idea how complex these genetic studies are.

So just with the publication of these papers recently, we now have a much more complete and detailed history of the first migrations into the Caribbean and exactly who these people were over time. We see that the migrants were a mosaic of cultures spreading out over 1,000,000 square miles and 700 islands going back 6,000 years or maybe even earlier; the genetic research continues using lab equipment that only those who study in Eurasia had before.

There are sixteen archaeological sites in Cuba, the Bahamas, Puerto Rico, Guadeloupe, and St. Lucia — classified as ‘Archaic’ or ‘Ceramic.’ The later Arawak-related people settled in the Bahamas, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Puerto Rico, Guadeloupe, St. Lucia, Curaçao, and Venezuela.

Some archaeologists pointed to dramatic shifts in Caribbean pottery styles as evidence of new migrations. But the Caribbean DNA study shows all of the styles were created by one group of people over time. Pictured: These effigy vessels belong to the Saladoid pottery type, ornate and difficult to shape. Source: Corinne Hofman and Menno Hoogland/Florida Museum of Natural History

No comments:

Post a Comment